Welcome to the Historic Daniels and Fisher Clock Tower!

This guide will help you explore Denver’s first skyscraper, and the views this 375 foot tall building provides. Follow the guide as you make your way through the Tower, and be sure to watch your step!

History of the Daniels and Fisher Department Store

Daniels and Fisher Department Store, with five floors, circa 1902 Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library, X-22869

Gold seekers came west in large numbers following the 1849 gold strike in California. Despite the fact that the land you now stand on was given to the Cheyenne and Arapahoe through a treaty, prospectors began looking for gold along their route west. In 1858 prospectors panning for gold at the confluence of Cherry Creek and the Platte River did find gold. Two years later nearly 5,000 gold-seekers were in the Denver area, and those miners needed supplies. Merchants, such as William Bradley Daniels, made an honest living selling to those miners. In 1864 Daniels rented a modest one-story wooden storefront on Larimer Street as his first store. Business was brisk and by 1869 Daniels built a three-story brick store at 1543 Larimer.

William B. Daniels wasn’t new to the retail industry. Born in Friendship, New York in 1825, he moved to New York City, where he started in the retail business. From there, he headed west, establishing a dry goods business in Iowa and opening a second location in Leavenworth, Kansas. He sent his brother-in-law, William Kenyon, further west to a little city called Denver, opening a store in October of 1864, where he sold picks, shovels and miner’s boots, among other items, to the gold seekers.

In 1872 William B. Daniels added a business partner, William Fisher, who had clerked at Daniel’s Iowa City store. Fisher kept late hours to capture the business of folks who worked during the day, frequently keeping the store open until 10:00 p.m. The partners relocated to Lawrence and 16th Street, an area quickly becoming Denver’s shopping district in 1875. Their new two-story department store was designed by Frank Edbrooke, who also built the Oxford and Brown Palace Hotels. Edbrooke placed the entrance to the store on the corner to capture traffic from both streets. Business at the new location did well, and by 1878 they employed 45 salesclerks, and 100 seamstresses who manufactured ladies’ clothing, undergarments and other items, while the second floor held an upholstery and carpet shop. By 1879 they added a fourth floor, and a fifth floor followed in 1893. For the first four decades, the store’s wholesale side was more profitable, outfitting small-town merchants and traveling salesmen that traveled throughout the West.

In 1879 Daniels saw an opportunity in another western boomtown, Leadville. Many in Denver got their start in Leadville, most famous of those Horace Tabor, whose success in Leadville led him to build the Tabor block at 16th and Larimer, just down the street from Daniels’ store. He selected a site at Third and Harrison Avenue, near another Tabor property, the Opera House. Bringing on a third partner, Joel W. Smith, the Leadville outfit was prosperous. Smith would own 100% of this store upon Daniels death. Our own Margaret Brown was employed at the Leadville, Daniels, Fisher & Smith store in 1886. She worked primarily in the new carpets, draperies and shades department. Her colleagues were quite fond of her, and she was a bright and exceptional worker.

Interior view of the Daniels and Fisher store in Denver, Colorado; shows displays of crystal and glass, 1902 Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library, X-22862

In the 1890s Daniels and Fisher held the title of largest retailer in Colorado. Organized around a central atrium, the store was lit by a large skylight, which allowed all the floors natural lighting. The first floor held dry goods; items like silks, lace, bedding, gloves, and underwear. The second floor held ladies clothing, children’s clothing, millinery, the tearoom and ladies sitting room. The third floor were the carpets, draperies, and furniture. Floors four and five were the wholesale operations. Clerks of both genders helped shoppers throughout the store, and female shoppers were aided using credit when making purchases, since women in that era did not have much cash of their own. Daniels and Fisher extended credit to women who were known to have the ability to pay, the balance sent to their husbands at the end of each month.

Interior view of the Daniels and Fisher store, 1902. Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library, X-22843

William B. Daniels, a millionaire and leading citizen, had a carriage accident in 1890 which led to a stroke and quick decline in his health. He died at age 65 on December 24th. Half of his cremated remains lie with his first wife, Elizabeth Knox at Rosehill Cemetery in Chicago, the second half were kept in a vault in the Denver store.

William Cook Daniels, the son of William B. Daniels, took over management of the store in 1897 following the death of the junior partner, William Fisher. He bought out William Fisher’s widow’s shares and became the sole owner of the store and set out to incorporate new improvements. He remodeled the facade, expanded the tearoom and moved it to the fourth floor, and introduced a bicycle department, jewelry department and floral shop. In 1898 he added a fifth floor to the building and modified the façade so that it appeared as one cohesive building in the Renaissance Revival style, so popular at the time. He also made operational changes, like creating an in-store school for the children that worked as stock boys, and cash boys and girls, so they did not miss their education due to their working hours. Employees were paid for the time spent in the school.

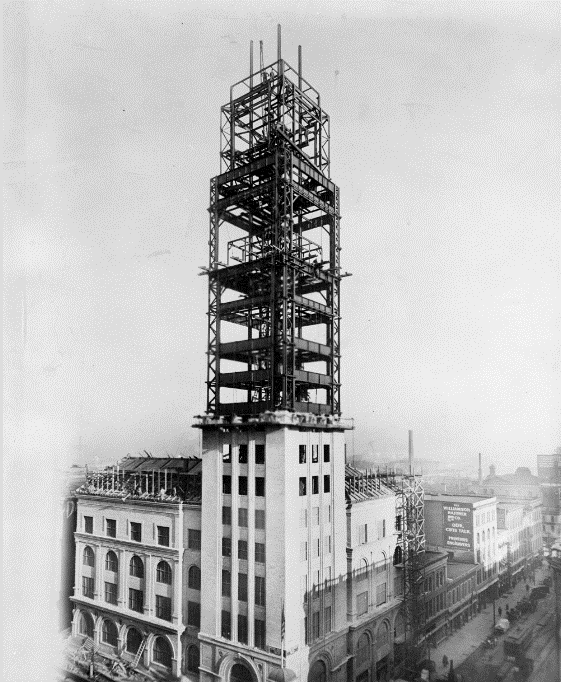

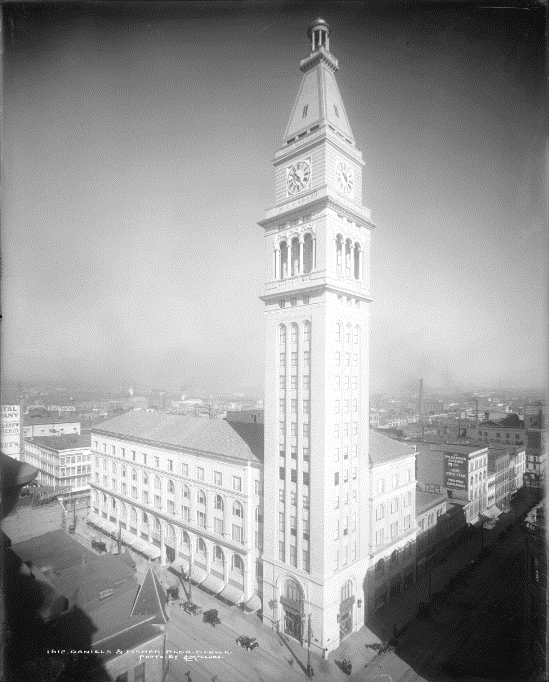

History of the D&F Tower

The clock tower was the last piece to be built. A cornerstone for the 5-story Daniels & Fisher department store, it also provided a secondary entry to the store, public observation deck and giant clocks on all four sides.  Modeled after the Campanile of St. Mark’s in Venice, the tower was designed by Frederick Junius Sterner and George Hebard Williamson. Building the Tower and changing the facade of the entire store to a buff brick, also made the store stand out among competitors like the Denver Dry Goods, which was built of the more common red brick. The store claimed its rank as the third-tallest building in the country. It remained the tallest building in Denver until 1958, when it lost its title to the First National Bank building on 17th and Welton.

Modeled after the Campanile of St. Mark’s in Venice, the tower was designed by Frederick Junius Sterner and George Hebard Williamson. Building the Tower and changing the facade of the entire store to a buff brick, also made the store stand out among competitors like the Denver Dry Goods, which was built of the more common red brick. The store claimed its rank as the third-tallest building in the country. It remained the tallest building in Denver until 1958, when it lost its title to the First National Bank building on 17th and Welton.

The Tower came about during Mayor Speer’s City Beautiful Movement, a desire to remake Denver in a more artistic fashion complete with art, parks and parkways. The floors of the Tower, while narrow, each had a purpose. The fifteenth floor housed the school, another floor the hospital, the male buying staff had a floor fitted with a gentleman’s club, billiard table and periodicals. The cash boys had a lounge to play games between shifts. The 14th floor, with its balconies served as a dining room for store functions.

The 20th floor was the observation deck. Up to 1,500 visitors a day paid a dime apiece to ride the elevator to the observation balconies on 20th floors and enjoy the unparalleled view.

Ever the commercial enterprise, Daniels and Fisher used the building of the Tower for publicity and advertising. For example, when the bell for the Tower arrived at Union Station from its Baltimore foundry, there was a parade as the 5500 pound bell made its way to first the Denver Post at 16th and Champa, and then back to Arapahoe St.

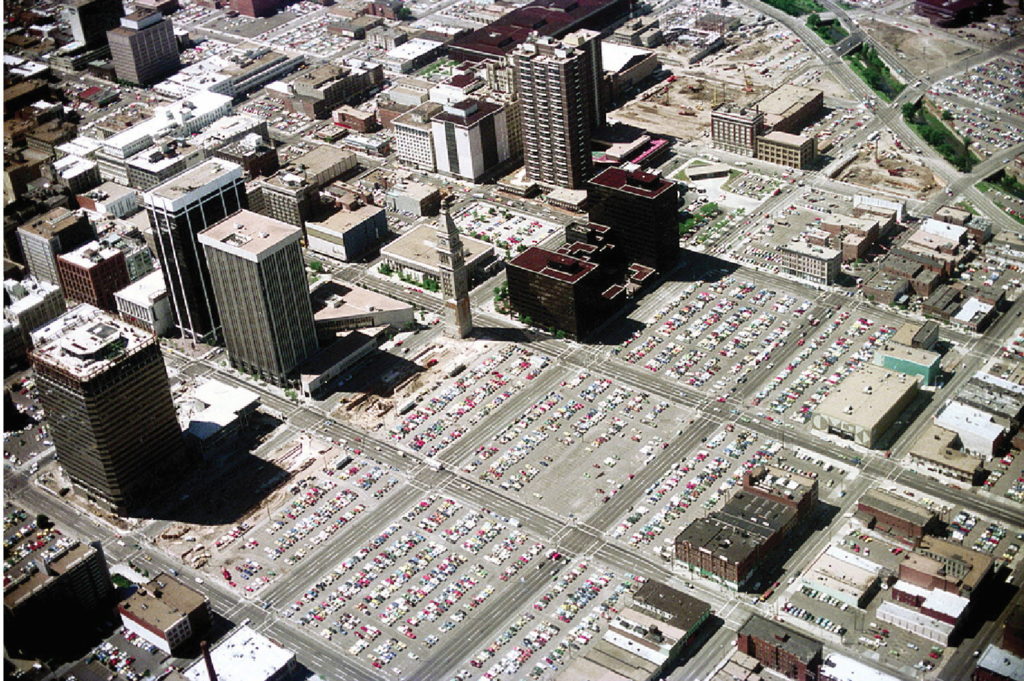

Urban Renewal

Lower Downtown Denver, c. 1930

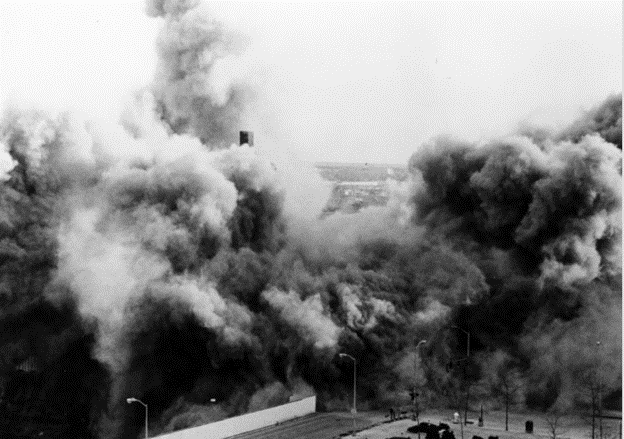

In the 1960s cities across the U.S. began demolishing historic buildings at an alarming rate. Frequently referred to as Urban Renewal, it had a major impact on Denver and its historic structures.

Lower Downtown Denver, c. 1976

As you can see when comparing these two photos of Lower Downtown Denver, Urban Renewal led to the demolition of 27 blocks, it would have been 28 but luckily Dana Crawford had the forethought to develop a plan for the 1400 block of Larimer.

The Daniels and Fisher Department Store, now vacant due to a merger with the May Company in 1953 was on the chopping block. And the Tower provides the only point of saliency between these two images.

Luckily for us local preservation-minded citizens advocated to keep at least the Tower portion of the store. The store was demolished in 1971. From the exterior of the Tower, the original connection to the main store is demarcated in red brick.

Luckily for us local preservation-minded citizens advocated to keep at least the Tower portion of the store. The store was demolished in 1971. From the exterior of the Tower, the original connection to the main store is demarcated in red brick.

Restoration of the D&F Tower

The Tower sat empty from 1971 to 1979, which left it vulnerable to looting. When restoration began many pieces of the building had to be replicated or replaced. The restoration of the tower took four years (1979-1983) and cost $10.5 million. It transformed floors 2-16 into fifteen private condominium offices.

Building Codes required the restoration team to replace the original “birdcage” elevator with a modern enclosed one. The Codes also made them fill the open atrium on the second floor with a solid panel of flooring. Compare the drawing of the lobby from 1911 with the lobby you see today.

Denver muralists Grammar of Ornament painted a custom ceiling panel so that the patched ceiling would match the rest of the highly decorative ceiling pattern.

17th Floor

The 17th floor is the elevator’s terminus. This was the case when the Tower was built in 1911, and remains true today. Visitors to the observation decks exited the elevator on this floor. Much of it was taken up by the swinging pendulum, suspended from the 18th. It is possible to see the views from this balcony, or if you prefer continue to the stairs to the 18th floor to see behind the clock faces.

18th Floor

Originally the 18th Floor was home to the clock’s inner workings. Built by the Seth Thomas Clock Company based in Connecticut for $8000. This device drove the 4 16 foot clocks, on each side of the Tower, and rang the 5 foot, 5ooo lb McShane Company bell. The clock workings held a long pendulum, which swung down on to the floor you just visited. Together these pieces kept the time of the 4 glass and iron clock faces with roman numerals on each side of the Tower. During the renovations in the 1980s these inner-workings were replaced by an electrically powered system controlled by a central computer. A 14 foot pendulum swung from the base of this device, making most of the 17th floor un-usable.

With 8′ long minute hands, each clock face is easily visible from the street, and the clocks continue to keep time today. From your current vantage point you can see 2 of the 4 faces, the 3rd you will see in the stairwell.

Views from the Observation Decks

South Views

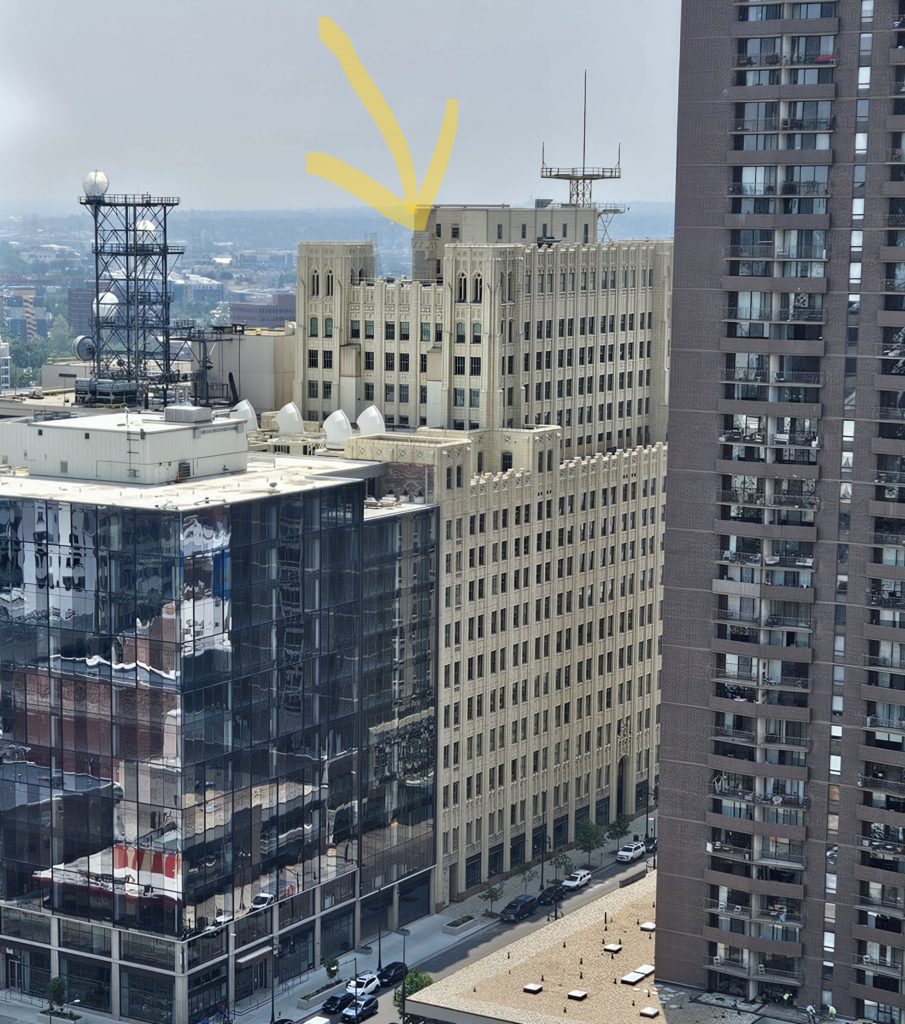

Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph

The building, which served as the headquarters of the seven-state region Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph (later Mountain Bell) from 1929 until 1984, was designed by William Bowman, in the Gothic Revival Style. It’s cream-colored terra cotta makes it stand out on Denver’s skyline. The entrance of the building features 13 murals showcasing telecommunications history by Colorado artist, Allen Tupper True which were painted in 1929.

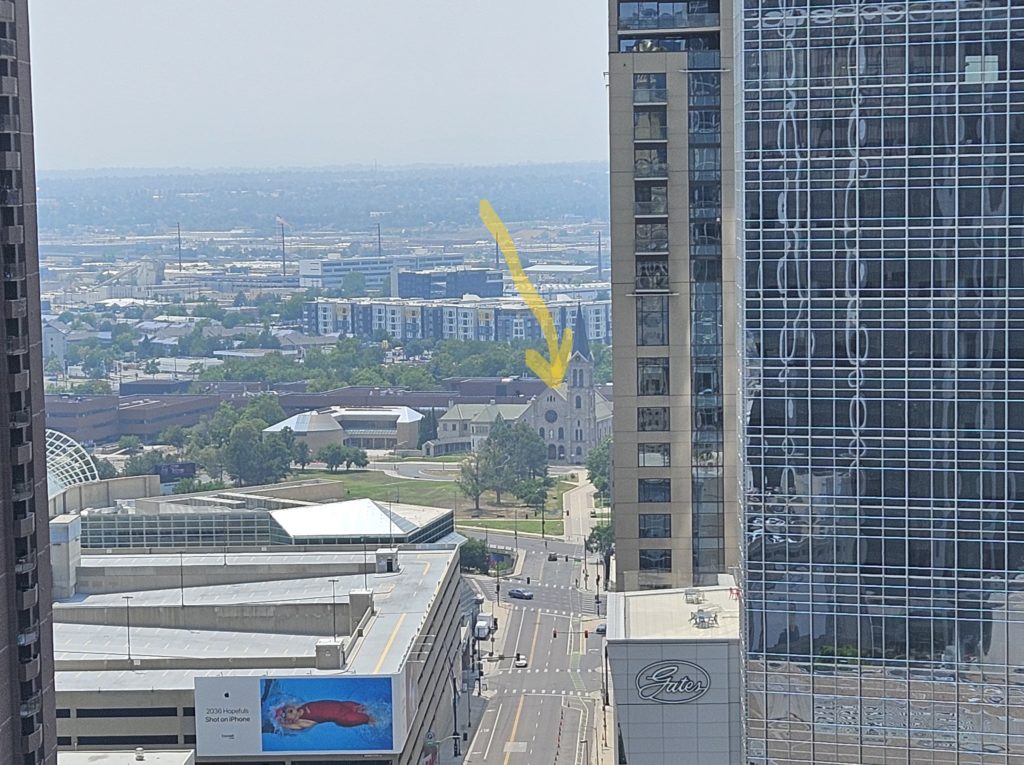

St. Elizabeth of Hungary on Auraria Campus

Established by Bishop Machebeuf in 1878, it was Denver’s second Roman Catholic church and served its growing population of German immigrants. This building was the church’s 2nd home, erected in 1898 in the Romanesque style, and built of rhyolite, a local stone quarried in Castle Rock, CO.

East Views

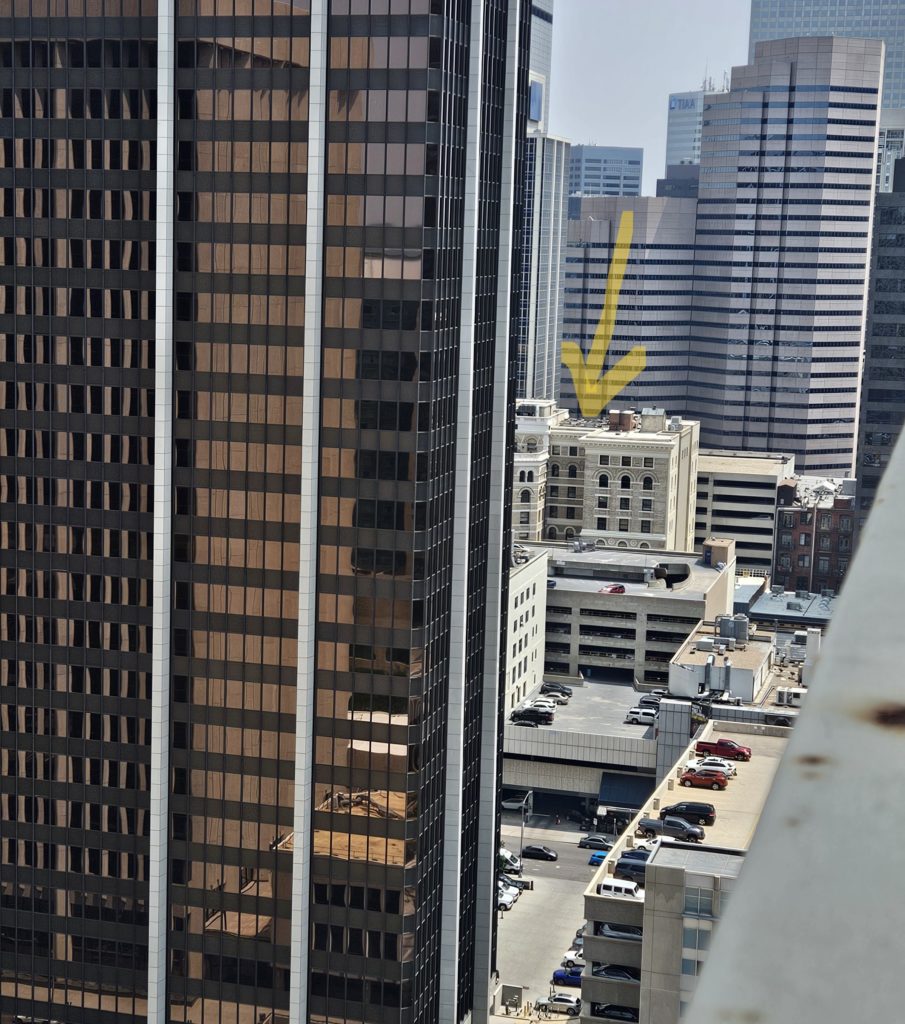

Equitable Building

When it was built in 1892, this building was the tallest in Denver. In 1911 that title was taken by the Tower you are currently standing in. The Equitable Building was built by Equitable Life Insurance. Designed by Boston architects Andrews Jacques and Rantoul it is the must luxurious office building in the state. No expense was spared, the building itself is two “E”s back to back, and the interior décor features more “E”s in the bronze staircase, Tiffany stained glass windows and ornate marble and tile. The building was the Governor’s Office, while the Capitol was under construction, and also the site of Women’s Bank of Denver.

Colorado State Capitol Building

When Colorado finally settled on Denver as its Capitol, local hotelier and developer Henry C. Brown donated this parcel of land to the state to build a Capitol building. The building, which opened in 1894 includes many local materials, including Yule Marble, Colorado Rose Onyx and gold leaf. Visible from this vantage point, the first gold was added in 1908, and it was re-leafed in 2012. The building still holds the offices of many state officials, including the Senate, House of Representatives and Governor’s Office.

University Building

Look carefully and try to spot a giant number 2 pencil in Denver’s skyline. In 2014 the A.C. Foster or University Building, transformed its smokestack into a larger than life pencil. Perhaps a nod to the fact that A.C. Foster, the original owner, donated the building to the University of Denver in the 1920s, who used it as an income-producing asset; the University sold the property in 1980. Today it is used as offices and businesses, including several jewelers.

West Views

Union Station

In the late 1870s four railroad companies decided to create a Union Station for all their trains. The result was Union Station, completed in 1881. Since then the central station has had many vers

ions, the large Beaux-Art building was added in 1914. From here you can see just the top of the station, with the icon neon “Travel By Train” sign, added in 1953, as a way to encourage train travel in the face of airplanes gaining more passengers.

Larimer Square

A little harder to see because of its lower buildings, Larimer Square is one block that was preserved from a movement to remove many of Denver’s historic buildings. The block is significant in that it is truly where the city was founded. Plotted by William Larimer in 1858, Larimer built his own cabin on the corner of Larimer and 15th Street. Today you can get a feel for the original street by visiting this newly created pedestrian area. Buildings like the Granite Hotel on the site of Larimer’s cabin show what Denver buildings from the 1870s and 1880s look like.

16th Street Mall

16th Street developed as Denver’s retail corridor, showcasing retails like Daniels and Fisher, Jay Joslin’s Department Store, Neusteter’s, the Denver Dry Goods Store and later the May Company. It was the place to shop in early Denver. In the 1980s the regional transportation needed a way to get travelers from the Civic Center to Market Street station, and the concept of a pedestrian mall took off. Originally designed by I.M. Pei, the street featured granite pavers which created a rattlesnake skin pattern. The design also created linearity among the light fixtures, trees, pedestrians and shuttles that ran up and down between the two hubs. In 2020 the city began redesigning the mall, changing the pavers, lighting and trees. From this vantage point the re-creation of a snake-like pattern along the mall is visible.

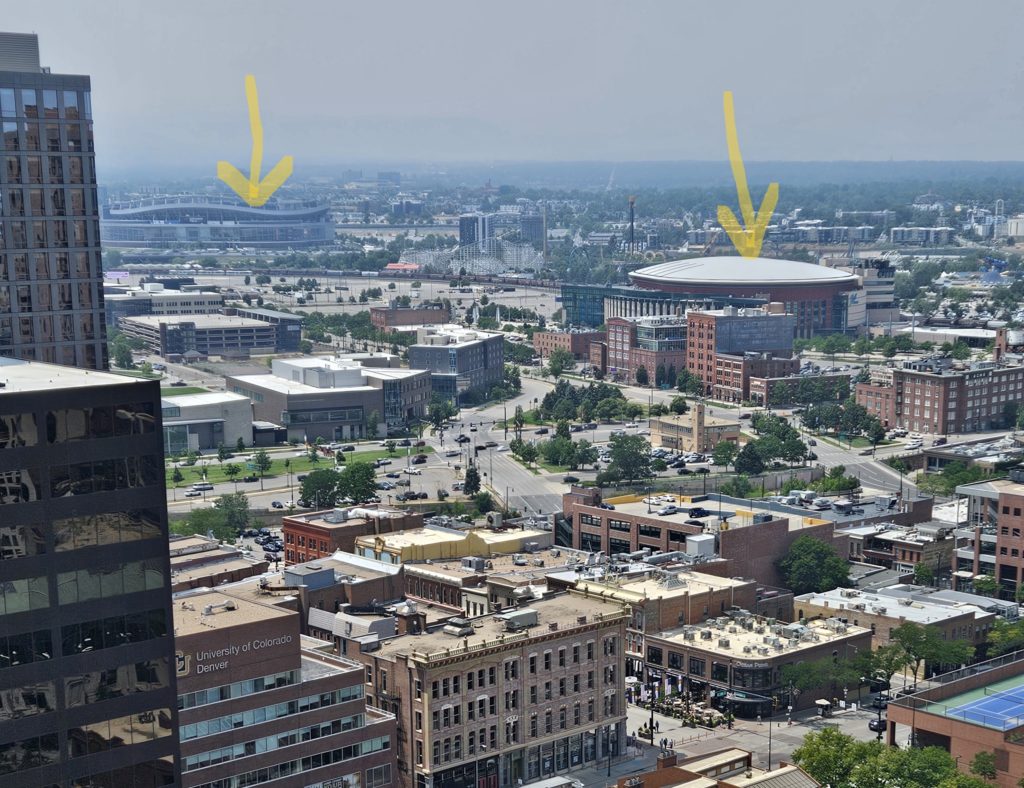

Stadiums and Ballparks

Stadiums and Ballparks

This view allows us to see where several of Denver’s professional sports teams play. The round stadium is home to the Denver Nuggets and Avalanche, and behind the Tower is Coors Field, home to the Colorado Rockies.

North Views

Lawrence Halprin Fountain

One of the 20th century’s leading landscape architects, Lawrence Halprin designed Skyline Park between 1972-1975. The park featured large geometric concrete planters and fountains meant to evoke rock outcroppings. Sunken below street level and surrounded by plantings, the park was envisioned as an oasis in the noisy city. In 2003 much of Halprin’s original design was lost, but these fountains remain.

Interested in learning more? The Denver Public Library has in their collection this account, written by a student for her composition class of her visit to the Tower in 1917.