CURRENT ISSUES

John Henderson House- Colorado’s First Black Architect

Celebrating the Life & Work of John Henderson

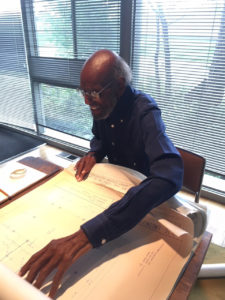

John Henderson looking at architectural drawings.

John Henderson was the first licensed African American architect in the state of Colorado. He worked on many institutional buildings in the City and County of Denver, but he was most proud of his family home in the Skyland/City Park North neighborhood, which he designed himself in the shape of an H.

Henderson passed away in June of 2018, but his dying wish was for his home at 2600 Milwaukee Street to be designated as a Denver Landmark. The Denver City Council approved the designation in November 2018, with John’s son carrying out his father’s dream and ensuring the home will be part of our city’s story, and architectural history, for many years to come.

Why it Matters

When John Henderson arrived in Denver in the early 1960s he saw opportunity- flipping through the phone book to find local architectural firms and ultimately securing a job at Fisher & Davis. He also encountered racism, and faced challenges as a Black architect working at an time and in a city where red-lining and de facto segregation limited opportunities for Black families and professionals. Within this context he was determined to leave his mark on the city, and to design a home and refuge for his family- one inspired by the work of his architectural hero, Mies van der Rohe, the acclaimed modernist.

The home, sitting on an expansive corner lot at 26th & Milwaukee, faces the City Park Golf Course and its modern style, clean lines, and large windows catch the eye. It is one of only a few Denver Landmarks designed after World War II, and during the hey dey of modernism in architecture, art, and furnishings. As older homes across Denver neighborhoods are scraped and replaced with larger homes, the designation ensures that John Henderson’s legacy remains alive and visible in our city.

Historic Denver’s Role

In 2017 friends of the Henderson Family contacted Historic Denver seeking assistance to fulfill John Henderson’s long-time hope that his own would be honored and protected. Historic Denver staff visited with John and his son at the home on several occasions, hearing his stories first-hand and recording an oral history that informed the designation application. Staff then prepared the nomination form on behalf of the family, and Denver City Councilman Albus Brooks sponsored the application as it moved through the Denver Landmark process and ultimately City Council.

While John Henderson passed away a few months before the designation became official, he lived long enough to know it was well underway. Historic Denver remains in touch with the family, and helped to arrange for John’s architectural drawings and materials to be donated to History Colorado’s permanent archives.

Background

In August 1959, Mr. Henderson was just “passing through” Denver to visit a college friend on his way to meet his wife, Gloria, in California to visit her family. He decided to call a few architecture firms to see what opportunities existed in Denver. The direction of his life would change with an interview at the Fisher & Davis architecture firm the next day. After talking to Gloria, he accepted the position and he, his wife, and their son, Lynn, made Denver their home. Mr. Henderson’s first project with Fisher & Davis was on the drawings for the Denver Federal Building and Courthouse (now known as Byron Rogers Federal Office Building), which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (5DV.1775). Mr. Henderson worked on the drawings for this building in 1960. Although he did not stay with the Fisher & Davis firm because the project was delayed due to the General Services Administration (GSA) approval process, this work launched Mr. Henderson’s architectural career in Denver. He worked for various other significant firms throughout the years, including Earl C. Morris; Wheeler and Louis architectural firm; James Sudler Associates; Victor Hornbein; and Edward White’s firm, Hornbein and White. Finally, he worked for the federal government in the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Shortly after Mr. Henderson received his license in October 1959, another African-American architect, Bertram A. Bruton, received his license in 1960.[1] Some sources have recognized Bertram A. Bruton as the first African-American architect in Colorado. This may be because Mr. Bruton first received his license in Colorado, whereas Mr. Henderson first received his license in Ohio a few years earlier, and then reapplied in Colorado where his license was transferred in 1959. Both men were trailblazers.

Henderson retired in 1981, but he continued as a consultant through the 1980s, creating drawings for a friend, Al Culbertson, who was a partner in Kobey-Culbertson Homes. During this time, Mr. Henderson designed many individual private residences, including the home of one of the Little Rock Nine, Carlotta Walls LaNier, in Cherry Hills Village in 1986.

Mr. Henderson’s architectural career in Denver spanned from 1959 through the 1990s. He designed federal buildings, institutional buildings such as schools and healthcare facilities, renovation projects, and private residences for prominent architectural firms. Among these diverse projects, Mr. Henderson was most proud of the design he created for his family home at 2600 N. Milwaukee St. in Denver, completed in 1963. This home was inspired by the architect he admired the most, Ludwig Mies Van der Rhoe, whose influence is visible in the Mid-Century Modern architectural style and elements of the home.

The Henderson House sits in the Skyland neighborhood north of 26th Avenue, also called City Park North, which was part of the 1938 Residential Security Maps (also known as Redlining Maps) creating segregated neighborhoods. In east Denver, 26th Avenue marked the boundary between white neighborhoods to the south and black neighborhoods to the north. This makes the location of the Henderson home all the more significant, as it stands directly on the line of de facto segregation, and sends a message of achievement as the design of the first African-American licensed architect in Colorado. Henderson continued to live in the home until his death . His home embodies a significant portion of Denver history in terms of the African-American population, the architectural development of Denver, and the way the city has grown and changed over time, as well as Mr. Henderson’s life, accomplishments and impact on Denver history.

In the News

I am Denver, July 2019

Denverite, November 18, 2018

Get Involved

A Historic Denver membership not only provides financial support so that our staff can work every day on behalf of historic places; it also demonstrates that our community cares. You can take action by becoming a member today.

Updated November 2019