Denver’s First Historic Cultural District to Honor the Chicano/a Movement

On August 2, 2021, Denver City Council designated the La Alma Lincoln Park Historic Cultural District, recognizing the historic and cultural significance of the neighborhood in Denver’s Chicano movement.

Why It Matters

La Alma Lincoln Park is not only one of Denver’s oldest residential neighborhoods, with a rare concentration of homes built before 1890, but it was also at the heart of Denver’s Chicano Movement, or El Movimiento, in the 1960s and 1970s. The neighborhood demonstrates the close connection between place and people, made tangible by the surviving structures set close together — diverse in their architectural styles yet maintaining a consistent pattern for 150 years. All are drawn together by the central role of the public park in the neighborhood’s core, today also named La Alma Lincoln Park.

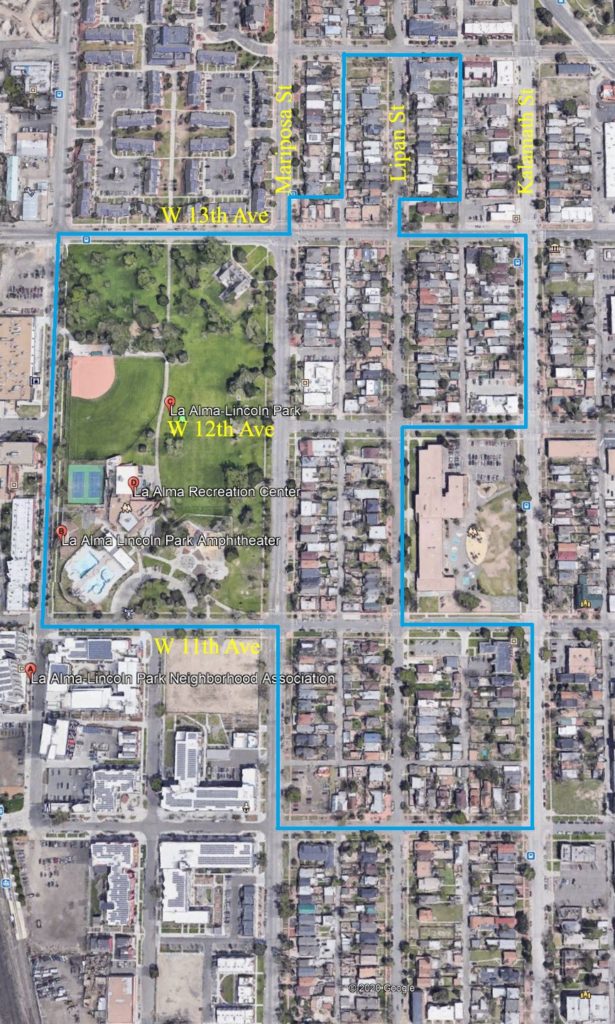

Map of the proposed La Alma Lincoln Park Historic Cultural District (boundary of the district is indicated by the blue line)

Historic Denver’s Role

Since 2017, Historic Denver has worked closely with neighborhood residents through one of our Action Fund projects. Neighborhood representatives applied to Historic Denver for funds and technical assistance to document the neighborhood’s history and buildings, and to seek strategies to protect and honor its unique historic context and cultural heritage. The work culminated in the proposal for a new cultural historic district in the neighborhood’s northern blocks along Lipan, Mariposa, and parts of Kalamath between 10th and 14th, approved in 2021. A group of current and former residents led the effort, with our support.

This designation was years in the making and long overdue. As Councilwoman Jamie Torres noted “Historic designation is our human attempt to ensure our roots aren’t forgotten…”

Background

The land was first home to the Apache, Ute, Cheyenne, Comanche and Arapahoe peoples. The area, near the Cherry Creek and the South Platte River, was along migratory paths, and groups set up seasonal encampments regularly. However, due to the floodplain, there was no permanent settlement in the immediate area until the beginnings of Denver and the town of Auraria.

In the 1870s, Alexander Cameron Hunt (referred to as A.C. Hunt or Governor Hunt) was among the most prominent and earliest of the area’s permanent residents. Hunt homesteaded what became the future park, known as Lincoln Park for its first century. The park became a central focal point as the neighborhood grew, with residential properties constructed to the north and south, and large industrial development to the west.

The neighborhood was built around key industries including the railroad (Denver & Rio Grande/Burnham Yards), flour milling (Mullen and Davis Four Mill), and other manufacturing industries. The neighborhood’s earliest residents — many of whom were German, Irish, Italian, Jewish or Mexican immigrants — were employed by the nearby industries, which were within walking distance of their homes. A tight-knit community developed, along with a strong sense of belonging to the neighborhood. Many of the homes in the new district date to this early period, with more than half constructed by 1900.

By the mid-20th century, due to new waves of in-migration, the neighborhood had a large population of Latinos, Hispanos and Mexican-American residents and homeowners, including many who became influential leaders of the Chicano Movement. Denver was at the forefront of the national Chicano Movement, inspired by many residents of this neighborhood. Many leaders and activists recall their youth in the neighborhood and time spent in or near the park. The Movement represents the convergence of independent issues: land rights, labor rights, long-term discrimination, opposition to the Vietnam War, civil rights as embodied in the Civil Rights Movement, cultural identity, lack of equity in education, and the inadequacy of the dominant political institutions to represent or address Chicano/a issues.

La Alma Lincoln Park homes, along with the federal housing projects that are no longer extant, were safe havens where Movement organizers and supporters lived, worked and gathered. The Movement was fostered in part through voluntary social service groups (many known as mutualistas) to assist Chicano/a families and help organize individuals and groups to be involved in the Movement.

One of the greatest concerns that galvanized the Movement was equity in education. The ongoing unequal access to facilities, the lack of bilingual programs, and disrespect for cultural heritage in public education programs sparked the blowout at Denver’s West High School in the spring of 1969. West High students and students from other Denver junior high and high schools gathered at West High and marched through the neighborhood to Lincoln Park over several days. These marches, along with other events and activities, made Lincoln Park historically important ground for Chicano/a rights in Denver and further made the La Alma Lincoln Park neighborhood an incubator for the Chicano Movement. The blowouts are also connected to Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales who was involved with the Neighborhood Youth Corps, which gathered in various locations in the proposed district. He launched the Crusade for Justice in 1966, which helped fortify the Chicano Movement locally and nationally.

Another significant sign of the Movement’s connection to the neighborhood is through the murals that exist on both public and private buildings. Artist Emanuel Martinez is a key figure in the creation of these murals and in developing the Chicano/a Mural Movement in Denver. One of the Chicano murals that still exists is on the La Alma Lincoln Park recreation center titled “La Alma,” designed by Martinez in 1978.

Most of the residences in the district are single-story cottages in modest versions of the Italianate and Queen Anne architectural styles constructed between 1879 and 1889. Among other modest styles here are the Terrace (usually two to six units), Dutch Revival, Foursquare, bungalow, Victorian cottage, and Classic Cottage residences. The vernacular homes were not built by recognized architects, but often reflect careful craftsmanship and popular architectural styles of their time in a simplified manner.

During the early part of the 20th century and increasing in the 1930s, Mexican-American, Hispano and Latino families moved into LALP in growing numbers. As new residents and families purchased or rented the older homes, they began to adapt the homes to meet their needs. Common adaptations include enclosing porches and adding dormers in order to create more living space. The classic iron fences enclosing the small front yards throughout the district were either maintained or replaced with more readily available material, such as chain link. Many of these changes reflect the ideals and economies of the people that altered them and took place as the Chicano Movement began to swell in the neighborhood in the 1960s and 1970s. Maintaining the aging homes as safe spaces for families, for gatherings, and for mutualistas, along with the culturally important front porch and front lawn areas, was a key ingredient to the strong sense of shared community.

The 1975 National Register for Historic Places nomination for The Westside Neighborhood including the proposed local district boundary, noting that, “Such clear evidence of how many Americans once lived provides us with a memory by which to judge the present and serves to put the outstanding mansions and public buildings that occasionally are preserved into context which is more accurate historically.” Nearly 50 years later, we can add to this context the story of this place, which is now layered with meaning by the generations that have called La Alma Lincoln Park home.

The research and application for the historic district were prepared by Fairhill & Co., with additional drafting by Tanya Mote and Shannon Stage. The neighborhood team spent significant time conducting outreach regarding this project, including hosting walking tours and coordinating several community meetings hosted by the city’s Landmark Preservation team to shape the proposal and create custom design guidelines that will support owners in preserving the layered built environment. Denver City Councilwoman Jamie Torres and former Councilman Paul Lopez were engaged throughout the process.

- Next City: Denver May Soon Create the Country’s First Historic District Honoring Chicano Movement

- Denverite: La Alma Lincoln Park moves closer to becoming the city’s second-ever historic cultural district

- Denver Fox 31: Denver neighborhood fights to become first historic district to honor Chicano Movement

Get Involved

A Historic Denver membership not only provides financial support so that our staff can work every day on behalf of historic places like this one — it also demonstrates that our community cares. You can take action by becoming a member today.

Updated May 2022